Homily: Reflections on Thomas Starr King by Arliss Ungar

The following is a homily given by Arliss Ungar, Chair of the Balázs Scholars Committee, former Chair of the Board of Trustees, and author of With Vision and Courage: Starr King School for the Ministry: The History of its First Hundred Years, during Tuesday Chapel Service on May 5, 2015.

Thomas Starr King was born in New York City on December 17, 1824. He was the eldest of the six children of Thomas Farrington King, a Universalist minister, and Susan Starr King, a woman of “character and intelligence, who…fostered the studious bent of her talented son.” He spent his boyhood in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and Charlestown, Massachusetts. There was no high school in Charlestown. As was the custom, he was tutored for college by the grammar school principal, a highly educated man.

Thomas Starr King was born in New York City on December 17, 1824. He was the eldest of the six children of Thomas Farrington King, a Universalist minister, and Susan Starr King, a woman of “character and intelligence, who…fostered the studious bent of her talented son.” He spent his boyhood in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and Charlestown, Massachusetts. There was no high school in Charlestown. As was the custom, he was tutored for college by the grammar school principal, a highly educated man.

Starr, as he was called, was 15 when his father died. He gave up all hope of attending college and divinity school. He worked as a clerk and bookkeeper at a store, assistant teacher, grammar school principal, then bookkeeper at the naval yard to earn money to support his mother and siblings. “…in the companionship of books, by protracted, solitary studies, through daily contact with men and affairs, and the stern discipline of sorrow, self-denial and responsibility, this ‘graduate of the Charlestown Navy Yard’, as he humorously called himself, acquired an education, and developed a character.” Among his mentors were Universalist ministers, Edwin Chapin, his own minister, and Hosea Ballou II, his “theological father”, who designed for him a systematic course of study for the ministry. Although Starr King had no earned scholastic degree, even from high school, he was highly educated. (Better trained for the ministry, said his friend and colleague, the Rev. Henry Bellows of New York, than the graduates of Harvard Divinity School.)

Starr King gave his first public address on the 4th of July, 1845 at the Medford Unitarian Church. He was twenty years old. In October of that year he preached his first sermon.

It was at this time that Theodore Parker, in recommending him, said, “…he has the grace of God in his heart, and the gift of tongues. He is a rare sweet spirit, and I know that after you have heard him you will thank me for sending him to you.” After a short apprenticeship filling the pulpit of a small Universalist church in Boston while its minister was away, he was called to the Charlestown Universalist Church where his father had been minister. “I preach,” he said, “to mature and aged men and women, who have seen me as a boy in my father’s pew, and who can hardly conceive of me as a grown man. I necessarily cannot command in that pulpit the influence which a stranger would wield.” Two years later, after an extended trip to the Azores to restore his health, he accepted the call to the Hollis Street Unitarian Church in Boston. King had not repudiated Universalism. His faith had grown to include Unitarianism. It was at this time that Starr King popularized the famous quip told him by a Universalist minister (probably Thomas Gold Appleton), “The Universalist… believes that God is too good to damn us forever; and you Unitarians believe that you are too good to be damned.”

“Throughout his career he refused to acknowledge any significant differences between the two denominations, seeing them as varieties of a larger liberal faith that encompassed them both” (See David Robinson).

In December of that year, 1848, he married Julia Wiggin of East Boston, “a woman of personal attraction, social gifts, and intellectuality.” Over the years, he often mentioned his wife and two children, Edith and Frederick, in his letters. He adored his children, speaking of them as I do about my grandchildren!

The Hollis Street church was torn apart by dissension over temperance and anti-slavery, an economic issue as well as a moral one. Starr King was brought in to revive the remnants of a once thriving congregation. “It is difficult,” said Henry Bellows, “to over-rate the prejudices and animosities which a violent ecclesiastical law suit had formented in [Hollis Street] Church; in which minister after minister had tried his hand with unavailing struggles, and to which Mr. King came as a forlorn hope. But he brought gifts, learning, rhetoric, courage and attractions equal to the occasion….” Starr King remained there eleven years.

He supplemented his meager salary by lecturing throughout New England, and beyond.

He became one of Boston’s finest orators, talking on such topics as Goethe, Socrates, Substance and Show, and Sight and Insight.

He renewed his health and his soul with vacations in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. His writings about their beauty and their legends became his only book, The White Hills, Their Landscape, Legends and Poetry. But his health was failing; he felt he could no longer keep up the pace. After months of consideration, he took a leave of absence from the Hollis Street Church and left Boston for San Francisco hoping, perhaps, for better weather, for a location which, by its remoteness, would relieve the temptation to lecture so much, and for a place where he could “be somebody”. “I do desire,” he wrote Bellows, “to be in a position where my labor would be of greater worth to the general cause than it can be in Boston.” He hoped he would not be so looked down upon because he had no earned academic degree. Edwin Whipple, his biographer and the editor of his sermons and orations, put it this way,

“An attempt for him to assume the position of leader of public opinion in Boston would have been crushed by the superciliousness of the educated and fashionable classes.” He wrote Bellows, “I do think we are unfaithful in huddling so closely around the cozy stove of civilization in this blessed Boston, and I, for one, am ready to go out into the cold and see if I am good for anything.”

In April 1860, Starr King and his family set sail for San Francisco, taking a train across Panama. There was no trans-continental railroad then, and no wireless to the West coast. San Francisco had grown “in only one decade from a mere frontier outpost to a bustling city that claimed 80,000 souls and was impatiently huffy when the new census only gave it credit for 56,000. It was proud of the fact that it enjoyed the highest per-capita income of any urban center on the North American continent…” Starr King described it as a struggle of homes over half a dozen sand hills. His wife had less pleasant things to say about Sand Francisco, as she called it.

Starr King served the San Francisco Unitarian Society until his death, not quite four years later. He preached twice each Sunday on Christian theology, or occasionally about such issues as patriotism, the beauty of Lake Tahoe, or who to elect governor (Leland Stanford). His parishioners paid off their debt within a year. Under King’s careful supervision, they built a beautiful gothic church which they dedicated in January, 1864 “in two successive services, to the Worship of God and the Service of Man.”

During the US Civil War, Starr King traveled the State by stage coach, using his skills as an orator and the power of his personality to shape public opinion in support of the Union. “It has been said by high authority that Mr. King saved California for the Union. California was too loyal at heart to make the boast reasonable; but it is not too much to say that Mr. King did more than any man, by his prompt, outspoken, uncalculating loyalty, to make California know what her own feelings really were.”

With his lectures throughout Northern California, he helped to educate the people–the San Francisco elite, laborers, Blacks, miners–about Socrates, contemporary poets, materialism or the beauty of nature. He gave tireless effort to raise money for the Sanitary Commission, which later became the Red Cross. He served as trustee for the forerunner of the University of California.

He continued his ministry and his crusades until his frail body, weakened by diphtheria and pneumonia, could no longer survive. On March 4, 1864 he died. He was barely 39 years old. On his death bed, he sent this message to his congregation, “Tell them that it is my earnest desire that they pay the remaining debt on the church. Let the church, free of debt, be my monument. I want no better. Tell them those were my last words and say goodbye to all of them for me.” He was deeply mourned and widely honored by the thousands of people who admired and loved him. At his memorial service “…with the flags at half-mast from public buildings and the shipping in the harbor, while a vast crowd of twenty thousand people surged in and about the church, we bade him a last farewell on earth.”

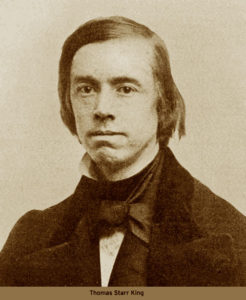

At Starr King School for the Ministry, the Unitarian Universalist seminary in Berkeley, California, the Reverend Thomas Starr King watches over us from his portrait in the entry hall. He’s a young man with soulful eyes, and lank, shoulder-length hair. An acquaintance (Curtis, a fellow Mason) described him as “an unimpressive, frail, homely young man with a shock of golden hair and penetrating grey eyes, less than 125 pounds in all.” I never thought of him as homely! His friends loved him; strangers sometimes found him unimpressive — until they heard his resonate voice and felt his passion and his kindness. Those favoring slavery and secession of the Southern states from the Union cringed at the “sledgehammer blows” of this oratory.

On New Years Day in 1854, when they were not yet 30 years old, Starr wrote to his dear friend, Randolph Ryer, We are fast getting to be old fogies, Randolph. Fourteen years since we first met….You, Randolph, always believed that I would come to something, when I did not dream that I had the capacity for adorning any pedestal. Your attachment has been a great comfort to me; your friendship has been pure enough to be accounted a choice privilege in any life. His friend was a New York businessman, an intellectual, a transcendentalist and, like Starr King, barely five feet tall. Some say he was a New England “free Negro,” but Glenna Matthews, an expert on Starr King, could find no concrete evidence of this. He saved Starr’s letters from their nearly 25 years of correspondence.

Many of Starr’s earlier letters to Ryer are in the Starr King School special collection at the Graduate Theological Union library near the school. I love to hold those fragile letters in my hands. The paper is discolored now; there are little pieces missing. The deep crease lines where the pages were folded to make their own envelope are sometimes torn. The red wax seals are wearing away. I take off my glasses and peer at the beautiful handwritten script, so hard to read now. Sometimes I laugh out loud. Once the Indian scholar sitting across the table looked so startled, I paused to read him Starr King’s description of the orthodox preacher’s voice which would remind one of the melody escaping from the friction of a saw and file (Jan. 9, 1841).

I have been known to wipe away a tear or two.

Starr, who believed that God was in all of nature, also believed that God hears our sighs and counts our tears (Divine Estimate of Death, 1854). He wrote his friend,

My dear Randolph,

I cannot tell you what gloom your letter of this morning cast over our home…. Thank God for the stray beam that struggles through the cloud of the morning. May it widen into a burst of sunshine! I know not how to write to you. Perhaps the darkness is settling heavily over your house and heart when these lines salute you. Whichever way, Randolph, feel that this note sends you the warmest and most sympathetic greeting of my hand and soul. Job’s comforters sat with him several days in silence when he was in trouble, attesting by their presence the sympathy which words could not utter, and which he did not care to hear. It is the heart and prayers of our friends that we need and prize in sorrow, not set words of counsel and comfort. What can we say but that God is good and acts in perfect Love? It is difficult to see that Love in the cold sweeping death wind that bears away a little one; but Christian meditation and the temper of prayer breaks rifts in the storm that let the heavenly sunshine through….God save you from the threatened desolation and give you pious hearts.

I am yours in sorrow as in cheer.

Starr. (Boston, May 5, 1854)

It’s been over 40 years since I’ve written to friends at the death of their child. I did not–I could not–remind them in their grief that “God is good and acts in perfect Love.” But I admire the strength of Starr’s faith and courage which allowed him to “speak his Truth in Love.” “Speaking the truth in love,” said a colleague, “was a text he seemed born to illustrate.” (Whipple)

There were other kinds of sorrow!

My Dear Randolph,

….I am quite unwell, but it is sickness of the mind, not the body…I may as well tell you the cause of my illness; it is a final parting with Frances under the most unpleasant circumstances. You may well imagine it was not of my seeking. How well I loved her, I never knew until now. God bless her….Hasten your coming my dear friend, we all anticipate much happiness from your presence. And none, be assured, more than

Your friend, Starr (July 1, 1845)

A year later he writes that he has been called to the Charlestown Universalist Church, and on page two, that he is engaged to Julia. She is a fine character, is capable of being well educated and is every way fitted to make a perfect minister’s wife (Aug. 27, 1846). I want to shout out into the quiet of the library, “But, Starr, do you love her?” Yes, I think he did. But it was not always easy. Julia, who often [broke] out in a storm of wrath may have had something to do with his comment, Our feminine reformers insist that things will not go right till the ladies are elected partially to represent the nation, which would relieve us about as pouring oil on a fire would soothe a conflagration (Sept. 1862).

At the dedication of the new Unitarian church built under his guidance in San Francisco, Starr described worship as a natural, noble, and precious expression of human feeling…This church, he said, is erected to train and feed the spirit of worship. Not only by hymns and prayers, but by the influence of instruction and appeal as well….The main purpose of the services …is to stimulate and refresh the feelings of wonder and awe, of obligation, gratitude, and trust before the Infinite (Jan.10, 1864).

Starr’s sermons were on theology and how to apply it to daily life. They did not follow Ralph Waldo Emerson’s prescription that “The true preacher can be known by this, that he deals out to the people his life, — life passed through the fire of thought.”

My Dear Randolph,

This morning I preached on Liberal Christianity as a positive faith, showing that all the positive elements which can belong to a religion are in ours, if preachers only have vitality enough to make them glow. It produced quite an impression on our people. O that we might wake them up to a feeling of the rich elements our faith contains, so that this weak, compromising twaddle would be banished from the pulpit and press… (September 10th, 1849).

Sometimes his sermons contained awesome descriptions of nature.

For many weeks the land has been afflicted (so it seems, at least, to our ignorance) by almost uninterrupted sunshine. From the Atlantic [Ocean] to the Mississippi [River] the sky has been hot, hard, and hollow over a parching soil. The hillsides are blasted with fever. The grass has been scorched. The fruits have shrunk. The trees are withering with thirst, and shedding shriveled leaves upon the burning winds. The streams are dwindling; brooks and ponds are drunk to their springs by the insatiable sun. No “ribands [ribbons?] of silver unwind from the hills.” The corn-harvest is smitten. The glorious promise of the early summer, pointing to full garners and cheap food, has died into the arid landscape of waste and destitution…(Lessons of the Drought, 1854). When I read this in my home church someone quipped, “That’s some weather report!”

In his sermons and in his orations, he spoke out for social justice.

….The question of absorbing interest to society itself is this–how shall the Church, which contains the regenerative principles of truth, be brought from its serene and comfortable elevation into redeeming contact with the streets, lanes, and cellars of the world. If we will not take up this problem of pauperism and ignorance in the spirit of Christian duty and love, and consider, through some constructive methods the rights of the poor, it will be pressed upon our self- interest as involving the existence, or at least the health of society (April 28, 1851).

I like that quote. I’ve used it in every talk on Thomas Starr King I have given.

When Starr was 19, he explained to his friend, You, Randolph … desire the social manifestations of Christianity as a means of raising the individual. I look rather to the elevation of the individual as one great means of improving society. Both tendencies are needed my friend, neither should exclude the other (Sept. 24, 1844).

Yet, years later he declared,

We are not intended to be separate, private persons, but rather fibers, fingers and limbs. The aim of religion is not to perfect us as persons, looking at each of us apart from others. The creator does not propose to polish souls like so many pins — each one dropping off clean and shiny, with no more organic relations to each other than pins of a card….

There can be no such thing as justice, until men, in large masses, are rightly related to each other… (Address to the Masons, May 1863).

He spoke out for racial justice.

In 1850, when the fugitive slave law requiring the return of captured slaves was passed, Starr King described it from the pulpit (in his own not so gentle way of dealing with injustice), as a hideous deification of what is base and wrong, and an open defeat in the heart of a Christian people of mercy and Jesus, by injustice and Satan… (Oct. 21, 1850).

Wherever we find many races brought together, he said, here God has his greatest work to do–there is room for the noblest work of Christianity ….The Almighty has a great mission for this nation–here the Church is to proclaim the equality of the races. Wherever the oppressed are congregated, there Christ is present–and not on the side of power

(Address to a “Negro” gathering, Aug.1, 1860).

Starr King found solace in the beauty of the natural world. When he was tired and discouraged, he traveled to the White Hills of New Hampshire, to Yosemite Valley, Lake Tahoe or to other places in California of serenity and beauty. He described this beauty in his sermons, orations and newspaper articles. He told his congregation, there can be no abiding and inspiring religious joy in the heart that recognizes no presence and touch of God in the permanent surrounding of our earthly abode (Lessons from the Sierra, 1863).

My Dear Randolph,

….The world, as the almighty has made it, is not such a world as a monk, a mystic, a broker or a Calvinist would have made. They would have left out the pomp of sunsets and the glory of dawns, the delicious tints and harmonic hues of flowers and meadows, the grace of movements, the witcheries which moonlight works, the spiritual fascination which the gleam of stars produces. The broker would say it is a useless waste of Heavenly chemistry; and would have gone for the cheapest furnishings (?); the Calvinist that it injures the religious faculty of man and would have robed the earth and hung the heavens in black and grey. But God thinks differently. His universe is not only an algebra for mathematicians, and a sermon for theologians, but also and equally, a poem for the taste and heart of man. And I cannot interpret beauty in any other way than as one evidence, and a splendid revelation, of God’s love (June 29, 1859).

A student at Starr King School asked me not long ago, “What was he like? Did he sometimes have doubts about his faith and his calling?” “His religious faith had no misgivings,” we are told. He believed in God, and in Jesus as God’s manifestation of himself on earth. He believed in an afterlife. His calling was to serve his church and his country. “He longed from an early age, to…give his life to the service of the church.” Which he did! He died from diphtheria and pneumonia when he was barely 39 years old, having committed what his future son-in-law termed the “slow suicide of overwork.” When cautioned to slow down, he replied, I have only one life to spend, and now is my time to spend it (Crompton).

He had no doubts about his faith and his calling, but he did have doubts about himself. He wrote to the San Francisco church, I am not conscious of any gifts, either of thought or speech, that can make my presence with you so desirable as you seem to think. He wanted desperately to “be somebody.” He told his friend, I mean to write a book on California that will make even you…believe I am somebody. He was somebody—somebody for whom statues were erected, and mountain peaks and churches and schools were named.

People ask me why the school was named for Thomas Starr King. His daughter and her husband were among the original founders of the School, but it wasn’t called Starr King School then. The official record says that the school wanted a name more euphonious than Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry and one that denoted, but did not say, both Unitarian and Universalist.

But let me give you my version. Perhaps Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry was renamed Starr King School for the Ministry to honor the Reverend Thomas Starr King because he was somebody. He was somebody who was small, frail and insecure, yet inspired his beloved country with his ideals and his actions. He was a religious leader of passion and compassion. He was somebody who was highly admired and deeply loved.

Why was the School named for Starr King? Because Starr King loved:

He loved his Unitarian and Universalist religion, its churches, its congregations, its children.

He loved his Christian faith, his family and his friends.

He loved his country with a fervor most of us will never know.

He loved adventure and action; affirmation and education.

He loved beauty and justice; words and wisdom.

He loved politics and preaching.

He loved mountains and music.

He loved ministry and raising money.

He loved hiking and humor; and he loved humanity.

Sometimes as I hurry out the door at Starr King School, I pause for a moment in the entry hall, look at the portrait of the Reverend Thomas Starr King and tell him “Thank you, Starr, for teaching all Unitarians by who you were; thank you for standing on the side of love.”

Download Reflections on Thomas Starr King.